Marriage Equality

Justice Anthony Kennedy writing the majority opinion on Obergefell v. Hodges, decided 5-4 that same-sex marriage is a right

Justice Anthony Kennedy writing the majority opinion on Obergefell v. Hodges, decided 5-4 that same-sex marriage is a right

The States’ Rights explanation is probably the most common deflection from the root cause of the war that killed the most Americans ever, more than all of the other wars the U.S. has fought combined.

And yes, the Civil War was a turning point in how people conceived the nature of this Republic. It crystallized the strong centralized nature of the federal government and it significantly curtailed the sovereignty of individual states (although this had been an ongoing process even prior to the Civil War, starting with the replacement of the Articles of Confederation with the Constitution.)

But the key question is, what right exactly did the secessionists want the states to exercise, free from federal interference?

You only need to look at the primary sources (as Ta-Nehisi Coates has done) to see that the secessionists fought primarily to preserve slavery.

This examination should begin in South Carolina, the site of our present and past catastrophe. South Carolina was the first state to secede, two months after the election of Abraham Lincoln. It was in South Carolina that the Civil War began, when the Confederacy fired on Fort Sumter. The state’s casus belli was neither vague nor hard to comprehend:

…A geographical line has been drawn across the Union, and all the States north of that line have united in the election of a man to the high office of President of the United States, whose opinions and purposes are hostile to slavery. He is to be entrusted with the administration of the common Government, because he has declared that that “Government cannot endure permanently half slave, half free,” and that the public mind must rest in the belief that slavery is in the course of ultimate extinction. This sectional combination for the submersion of the Constitution, has been aided in some of the States by elevating to citizenship, persons who, by the supreme law of the land, are incapable of becoming citizens; and their votes have been used to inaugurate a new policy, hostile to the South, and destructive of its beliefs and safety.

…

…Mississippi:

Our position is thoroughly identified with the institution of slavery—the greatest material interest of the world. Its labor supplies the product which constitutes by far the largest and most important portions of commerce of the earth. These products are peculiar to the climate verging on the tropical regions, and by an imperious law of nature, none but the black race can bear exposure to the tropical sun. These products have become necessities of the world, and a blow at slavery is a blow at commerce and civilization. That blow has been long aimed at the institution, and was at the point of reaching its consummation. There was no choice left us but submission to the mandates of abolition, or a dissolution of the Union, whose principles had been subverted to work out our ruin…

…

Louisiana:

As a separate republic, Louisiana remembers too well the whisperings of European diplomacy for the abolition of slavery in the times of annexation not to be apprehensive of bolder demonstrations from the same quarter and the North in this country. The people of the slave holding States are bound together by the same necessity and determination to preserve African slavery.

…

Alabama:

Upon the principles then announced by Mr. Lincoln and his leading friends, we are bound to expect his administration to be conducted. Hence it is, that in high places, among the Republican party, the election of Mr. Lincoln is hailed, not simply as it change of Administration, but as the inauguration of new principles, and a new theory of Government, and even as the downfall of slavery. Therefore it is that the election of Mr. Lincoln cannot be regarded otherwise than a solemn declaration, on the part of a great majority of the Northern people, of hostility to the South, her property and her institutions—nothing less than an open declaration of war—for the triumph of this new theory of Government destroys the property of the South, lays waste her fields, and inaugurates all the horrors of a San Domingo servile insurrection, consigning her citizens to assassinations, and. her wives and daughters to pollution and violation, to gratify the lust of half-civilized Africans.

…

Texas:

…in this free government all white men are and of right ought to be entitled to equal civil and political rights; that the servitude of the African race, as existing in these States, is mutually beneficial to both bond and free, and is abundantly authorized and justified by the experience of mankind, and the revealed will of the Almighty Creator, as recognized by all Christian nations; while the destruction of the existing relations between the two races, as advocated by our sectional enemies, would bring inevitable calamities upon both and desolation upon the fifteen slave-holding states….

There is some evidence that the States’ Rights explanation exists only as a post-hoc justification for Jim Crow.

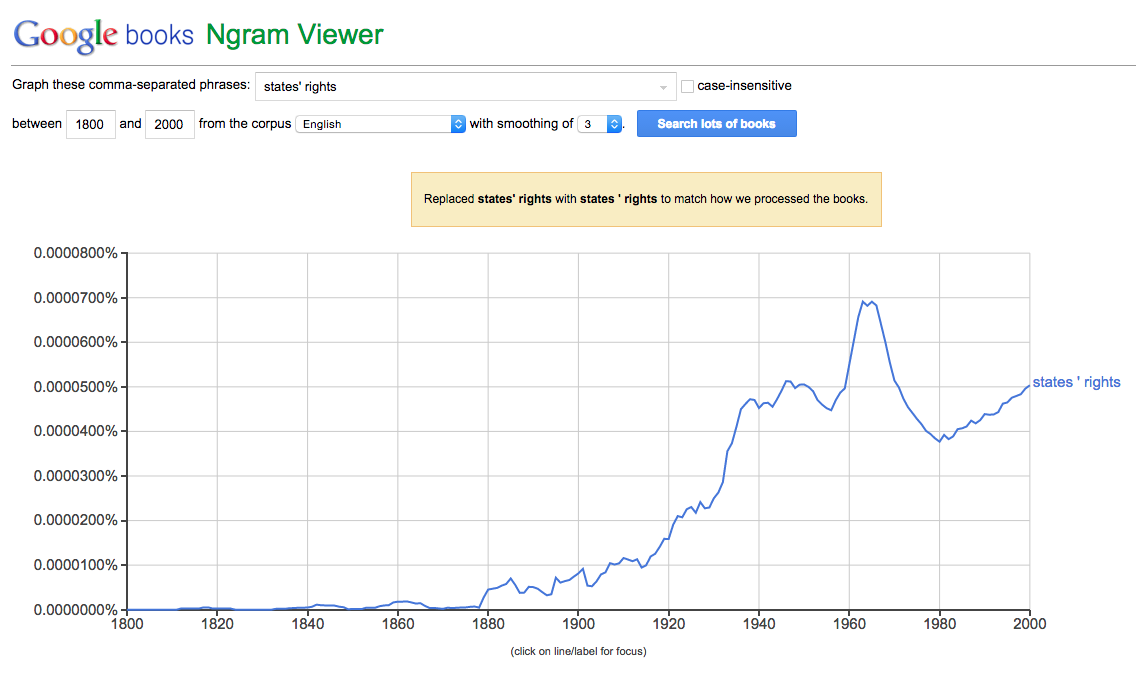

For starters, the phrase “states’ rights” seems to peak exactly as the Civil Rights Movement started taking off, with very scant mention during the Civil War itself.

But raw data mining is probably not as persuasive as historians poring over the primary sources.

Why We’re Finally Taking Down Confederate Flags • 2015 Jun 24 • Adam Serwer • BuzzFeed

As historian David Blight writes in his 2001 book Race and Reunion, in the aftermath of the Civil War and Reconstruction, former Confederates and their supporters waged a propaganda campaign to shape American historical memory. The result was a popular understanding of the war and its aftermath that glamorized the valor of Confederate soldiers, downplayed slavery as a cause of the war and cornerstone of the Confederacy, recast Reconstruction as a period of tyranny and ‘black domination,’ and justified the violent disenfranchisement and dispossession of black Americans for decades to come.

…

Even after the narrative of a benign and honorable Confederacy fell out of favor with historians, it continued to dominate American popular culture in film and literature, from The Birth of a Nation to The Dukes of Hazzard. The damage wrought by this interpretation of history is immeasurable. It is only now unraveling.

…

Most important, it was always untrue: Slavery was the cause of the war, white supremacy was the cornerstone of Confederate society, the individual valor of Confederate soldiers cannot hide that the cause for which they fought was one of the worst in human history, their defeat was not solely due to the North’s structural advantages, and they — not the Union — were the aggressors.

…

Shortly after the war, Blight writes, former Confederate Gen. Jubal Early gained control of the Southern Historical Society and used it to ‘launch a propaganda assault on popular history and memory.’ Later groups like the United Confederate Veterans and the United Daughters of the Confederacy worked to ‘control historical interpretation of the Civil War.’ In this interpretation, popularly known as ‘Lost Cause’ mythology, the Confederacy was fighting for some vague conception of liberty, not the right to own slaves; its soldiers were unparalleled warriors defending their homeland who were only defeated because of the Union’s structural advantages; and the postwar subjugation of black Americans was a necessary response to lawlessness. Professional historians like those of the late 19th/early 20th century Dunning School bolstered the popular perception that granting equal rights to black Americans after the war was an immoral and tragic error, thus justifying the imposition of racial apartheid in the South.

The blurb on The Dunning School: Historians, Race, and the Meaning of Reconstruction on Amazon has this to say:

From the late nineteenth century until World War I, a group of Columbia University students gathered under the mentorship of the renowned historian William Archibald Dunning (1857–1922). Known as the Dunning School, these students wrote the first generation of state studies on the Reconstruction―volumes that generally sympathized with white southerners, interpreted radical Reconstruction as a mean-spirited usurpation of federal power, and cast the Republican Party as a coalition of carpetbaggers, freedmen, scalawags, and former Unionists.

Edited by the award-winning historian John David Smith and J. Vincent Lowery, The Dunning School focuses on this controversial group of historians and its scholarly output. Despite their methodological limitations and racial bias, the Dunning historians’ writings prefigured the sources and questions that later historians of the Reconstruction would utilize and address. Many of their pioneering dissertations remain important to ongoing debates on the broad meaning of the Civil War and Reconstruction and the evolution of American historical scholarship.

This groundbreaking collection of original essays offers a fair and critical assessment of the Dunning School that focuses on the group’s purpose, the strengths and weaknesses of its constituents, and its legacy. Squaring the past with the present, this important book also explores the evolution of historical interpretations over time and illuminates the ways in which contemporary political, racial, and social questions shape historical analyses.

From the wikipedia page on the Dunning School:

Adam Fairclough, a British historian [whose expertise includes Reconstruction], summarized the Dunningite themes:

All agreed that black suffrage had been a political blunder and that the Republican state governments in the South that rested upon black votes had been corrupt, extravagant, unrepresentative, and oppressive. The sympathies of the “Dunningite” historians lay with the white Southerners who resisted Congressional Reconstruction: whites who, organizing under the banner of the Conservative or Democratic Party, used legal opposition and extralegal violence to oust the Republicans from state power. Although “Dunningite” historians did not necessarily endorse those extralegal methods, they did tend to palliate them. From start to finish, they argued, Congressional Reconstruction—often dubbed “Radical Reconstruction”—lacked political wisdom and legitimacy.

Historian Eric Foner, a leading specialist, said:

The traditional or Dunning School of Reconstruction was not just an interpretation of history. It was part of the edifice of the Jim Crow System. It was an explanation for and justification of taking the right to vote away from black people on the grounds that they completely abused it during Reconstruction. It was a justification for the white South resisting outside efforts in changing race relations because of the worry of having another Reconstruction.

All of the alleged horrors of Reconstruction helped to freeze the minds of the white South in resistance to any change whatsoever. And it was only after the Civil Rights revolution swept away the racist underpinnings of that old view—i.e., that black people are incapable of taking part in American democracy—that you could get a new view of Reconstruction widely accepted. For a long time it was an intellectual straitjacket for much of the white South, and historians have a lot to answer for in helping to propagate a racist system in this country.

Yes, saying the Civil War was fought over slavery may be an oversimplification in the sense that it does not necessarily examine the historical context and it is frequently imbued with the simplistic assumption that the Union was Good and the Confederacy was Evil, but it also has the advantage of being true.

And while it is also true that people in both the Union and the Confederacy generally believed in white supremacy, this does not negate the fact that the Confederacy seceded primarily because Southerners believed that the inauguration of Abraham Lincoln and the ascendancy of the Republican Party heralded the total and complete abolition of the practice of slavery. Every other explanation is secondary and/or post-hoc.